Banks face mixed outcomes as a tight global economy runs its course and new headwinds lurk on the 2024 horizon. Asia Pacific banks look brighter than they did at the end of 2022, reflecting improved economic conditions. Still, as expected, a few Asian banks navigate narrow corners as their economies puff across the annual finish line. However, African economies have had tougher situations, and their banks have been pulled into more difficult realities.

Fortunately, Nigerian banks have turned out better than the economy. While the economy’s growth rate fell from 3.54% in Q4 2022 to 2.31% in Q1 and 2.51% in Q2 before rising to 2.54% in Q3 2023, banks have seen their financial books grow steadily as top and bottom-line earnings rise. Earnings for the banking industry have grown 44% annually over the last three years. Nigerian bank average prices have risen by 97.4% in the past year and by 86.9% year to date (YTD). The banking sector Index of the Nigerian Exchange Group (NGX) has risen from 2.60% in the first trading day of January to 102.03% YTD as of December 14, 2023. The rise in the Banking Sector Index reflects an improvement in their business fortunes. So why are Nigerian banks brooding over recapitalisation either by Rights Offers (new money raised from existing shareholders), or Initial Public Offerings (new money raised from new shareholders), or mergers?

At the heart of the recapitalisation conversation is the issue of the size of bank equity and tier 1 capital, given the requirements of Basle III. Analysts have questioned the adequacy of the size of Nigerian banks’ equity in the face of the naira’s depreciation and the government’s intention to attain a US$1trn economy over the next seven years. The result is that the government must achieve a gross domestic product (GDP) growth of at least 11.14% annually. To support this growth, Nigerian banks must increase their lending sizes and identify big-ticket transactions that could lead to faster-paced growth. One calculation is if N25bn was the threshold for banks when the naira to dollar exchange rate was N130.15 in 2005 (the first recapitalisation of banks in the 2000s era), with the exchange rate at N1000 to a dollar, the adjusted capital base of banks should be roughly N800bn. The new calculated base would merely keep the relative equity size of Nigerian banks where they were 18 years ago.

Proshare analysts have pointed out that good banks may come in different sizes. Setting a standard size for all banks may not be systemically optimal. Indeed, adopting a one-size-fits-all approach may have unintended consequences, as in the early 2000s, banks with governance challenges with N2bn capital base suddenly had more severe problems when they got the large recapitalisation boost of N25bn to play with as they lost their way to becoming toxic asset dumpsites. It took the stern hand of CBN’s erstwhile governor, Khalifa Sanusi Lamido Sanusi III, to set the banks straight and reestablish systemic confidence in 2010. The Sanusi action came to a mere half-decade after the Chukwuma Soludo-led CBN decision to engineer the merger and recapitalisation of banks in 2005, shrinking the number of banks from 89 to 25 with a minimum capital base of N25bn. After eighteen years, Soludo’s N25bn threshold appears to have run its course and requires reevaluation.

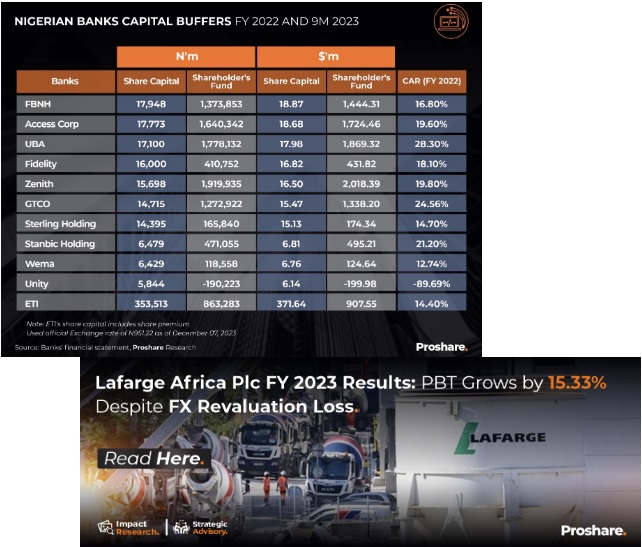

The issue, however, is that with a slow-growth economy (2.54% as of Q3 2023) and inflation in the upper double digits (27.33% as of October 2023), some analysts have argued that the timing of recapitalisation must be handled carefully to prevent a disruption to the financial system that could worsen economic outcomes. The refrain is sensible but not conclusive. As of the financial year end (FYE) 2022, none of Nigeria’s Tier 1 banks listed on the Nigeria Exchange Limited (NGX) had a share capital of N25bn despite significant shareholders’ funds. First Bank Holding Company (FBNH) had the largest share capital of N17.948bn, followed by Access Holding Company (Access Corp) of N17.773bn.

Nevertheless, both banks had shareholders’ funds above N1trn. In other words, for the larger banks, recapitalisation would mean a reclassification of their reserves and restatement of share capital. In this light, analysts expect that in 2024, several banks will offer bonus shares to existing shareholders, while a few might opt for fresh Rights Offers (purchasing more shares by existing shareholders).

The Liquidity Bungee Jump

Several Nigerian banks advertise consistent quarterly profits, but a few challenges restrict their growth and bottom lines. The problems include liquidity challenges in the foreign exchange market, relatively low capitalisation, high and constant discretionary CRR debt, and increased competition from emerging neo-banks. Before the recent signal from the Central Bank of Nigeria (CBN) that banks may be made to recapitalise, analysts have called for a recapitalisation of the Nigerian banking industry to support their capacity to finance big-ticket transactions, shore up their capitalisation in dollars and reposition them for sustained shareholder value. While the market awaits details from CBN on the new minimum capital base of banks, a few banks have raised fresh equity, and some have announced plans to strengthen their capital (through a Rights Issue, which offers new shares to existing shareholders, possibly at a discount).

The Rising Tide of Raising Capital-The Rights Ways

Following the conclusion of the share capital raise of Fidelity Bank through a Private Placement of 3.04bn ordinary shares of 50k each, Shareholders of FBNH have also resolved that the company’s issued share capital be increased from N17.95bn of 35.90bn ordinary shares of 50k each to N22.43bn, an addition of 8.97bn ordinary shares and that there should be a capital raise of up to N150bn through Right Issue. Wema Bank Plc has also submitted and gotten approval from the NGX to list a Rights Issue of 8.5bn ordinary shares of N0.50 each at N4.66 per share (based on two new ordinary shares for every three ordinary shares already held by shareholders). These moves align with the call for banking sector recapitalisation since the intrinsic and dollar values of the current capital requirement have been eroded and are too weak to withstand negative shocks or finance big-ticket transactions. Some analysts have argued that many banks’ inability to meet the current N25bn capitalisation portends enough threats to the financial system. Others argued that the banks are capitalised enough for the country’s current development and should not be the victim of the country’s FX challenges. A Highcap Securities analyst noted, ‘So far, bank financials figures show that many are already over-capitalised. Their balance sheets are quite healthy and impressive.’ For banks raising new capital, this would support growth prospects, and the Right Issue approach could preserve the relative share of existing shareholders’ stakes. However, the pre-emptive Rights waiver on undersubscribed shares could dilute the shareholders’ stake.

Nigerian banks have a history of raising capital through various means, such as Public Offerings, Private Placements, Rights Issues, and Mergers and Acquisitions (M&As), for reasons that include regulatory orders, balance sheet expansion, and risk-bearing capacity strengthening. More broadly, the compelling reasons for regulatory order to recapitalise banks are:

- To meet the regulatory minimum capital adequacy ratio and mitigate risks like credit, market, operational, and liquidity risks. The capital requirement measures the bank’s ability to absorb losses and protect depositors and is currently set at 15% CAR for systemically important banks and 10% for other banks.

- Support banks’ capital needs to fund their lending activities, invest in new products and services, and enter new markets, all necessary to finance developmental goals.

- Enhance operational efficiency and resilience, which are needed to improve financial technology infrastructure, digitise processes, and optimise cost structure.

- Create value for shareholders and stakeholders.

Recapitalisation: Of Share Capital and Shareholders’ Funds

Nigerian banks have evolved since the 2005 bank recapitalisation, when the minimum paid-up capital was raised to N25bn from N2bn. However, the exchange rate volatility has significantly eroded the value of the capital. All the listed banks have a share capital below N25bn, with FBNH having the highest at N17.95bn and Unity Bank having the least at N5.84bn. In dollars, the share capital is lower than US$20m as FBNH has $18.87m and Unity has US$6.14m. Some analysts have argued that the share capital size is insufficient to fund a mega project to achieve the targeted N1trn gross domestic product (GDP). Hence calling for another recapitalisation.

Meanwhile, the shareholders’ funds have improved over the years, and five banks have above N1trn, closely attaining the N2trn mark. Banks’ robust retained earnings have supported the continuous growth of the shareholder’s fund. Interestingly, most listed Nigerian banks comply with the Basell III capital adequacy ratio requirement, far above the 10.5% minimum requirement. UBA has the highest at 28.30%, and Wema has the lowest at 12.74%, excluding Unity Bank and other unlisted banks with negative CAR. The higher CAR might suggest a stronger capital position and ability to meet obligations. However, analysts still believe that the banks require fresh capital injection to drive key sectors of the economy. The recapitalisation process should follow a structured, lengthy time frame to avoid a reoccurrence of the 2005 era, which led to large mergers and acquisitions

(see table 1 below).

Implications for Minority Shareholders

According to a financial analyst, Olatunde Amolegbe, raising new shares through a right issue or public offering leads to lower earnings per share initially due to a larger amount of shares outstanding, but this will recede as the bank does more business and makes more money. The typical market reaction to recapitalisation is a slowdown in secondary market activities in the issuer’s shares since investors know that new shares will typically be issued at a discount, and they can buy cheaper.

Rights Issues present an open door to existing shareholders to exercise buying rights of new shares in proportion to their existing shareholdings and at a discounted price. Minority shareholders also have these open doors presented before them and may decide to participate in the right issue even though they are not obliged to do so. However, choosing to participate or not to participate will have crucial implications.

- Right issues can potentially dilute minority shareholdings or ownership percentages. Dilution of minority shareholdings becomes possible when minority shareholders do not participate in the rights issue and, as such, reduce the shareholders’ equity stake in the company.

- The dilution of a minority shareholder’s holdings reduces the percentage of shares owned and potentially the shareholder’s rights and voting power. Voting rights may, however, be increased with minority shareholder’s decision to participate in the rights issue.

- Shareholders can trade the rights allocated to them on the domestic stock exchange. This affords the shareholders who choose not to partake in the right issue the discretion to determine whether to divest their rights, potentially realising profits or incurring losses contingent on prevailing market conditions, or to exercise their rights to acquire additional shares.

- An allotment of additional shares through the right issue may be unfairly prejudicial due to possible concerns related to share dilution. Such dilution of claims held by minority shareholders is conceivable when they are precluded from participating in the rights issue, diminishing their equity stake in the company. Sections 343-346 of CAMA 2020 (amended) grant minority shareholders legal recourse in case of prejudice.

- Concerns may arise among minority shareholders regarding the transparency and execution of the rights issue. Companies must engage in effective and transparent communication, elucidating the rationale behind the rights issue, its repercussions on current shareholders, and the planned utilisation of the raised capital. Such communication can influence earnings per share.

- Increasing the number of shares in circulation can shape the market’s assessment of a company’s financial well-being and outlook. If investors construe the rights issue as a favourable indicator, it can positively affect the company’s overall valuation and shareholders’ positions.

Price Movement: Rounding up Investors’ Sentiments

The announcement of the Right Issues sparked a fair movement in stock prices. According to a market analyst, ‘the market has accepted the announcement of the Fidelity Bank and FBN rights issue in good faith, as their share price has increased. This means they will do more for the economy and empower businesses if they access more funds. The major fear in FBN is the power struggle between major shareholders, which has impacted the share price in the market. Fidelity is going well with no issues, while regulators must pay close attention to the FBN development as it concerns the major shareholders.’

Following Fidelity Bank’s decision to increase its share capital to 3.2bn ordinary shares, its share price rose from N4.79 on July 4 to about N9.05 on December 7. Similarly, FBNH’s share price soared from N11.05 on October 11 to N29.4 on December 6, 2023, propelled by the bank’s announcement to raise N139bn in additional capital through a Rights Issue (see chart 1 below).

Chart 1:

Analysts’ Thoughts – Capital Requirements and Financing Development

The call for bank recapitalisation has elicited mixed opinions. A few analysts have argued that bank recapitalisation is unnecessary and represents poking a finger into the eye of an imaginary storm. They argue that if a system is not broken, there is no point in fixing it. The school’s advocates argue that Nigerian banks are performing exceptionally well, noting that they are prudentially sound and financially profitable. Raising their capital base would reduce investors’ return on equity (ROE) and push down equity prices.

According to David Adonri of Highcap Securities, ‘banks have become over-capitalised due to the windfall from recent market reforms, while the real productive sector has become undercapitalised. Ordinarily, the proposed recapitalisation exercise should be directed at the real sector, not banks. Further, the migration of financial assets to the banking sector may reenact what happened in the past when the absorptive capacity of the real sector could not clear the excess cash in bank vaults. That eventually caused an asset bubble in the Capital Market and Housing sector. Banks are already concerned about the safe deployment of their huge funds, and capital expansion could reduce their returns on investment.’

Another school of thought argues that banks need to strengthen capital bases in a growing uncertain world to cope with potential shocks to short to medium-term loan assets. The proponents of this view argue that with Basle III compliance becoming of greater importance (as countries consider meeting the requirements of Basle IV), Nigeria’s bank leverage should be reduced by larger equity amounts. The bigger the bank equity, the lower the bank leverage and as a corollary, the lower the returns on equity (ROE). However, equity returns are only helpful if banks are safe. This school insists that bank equity must be raised in volatile exchange rates, high import dependence, and high inflation rates. Proshare analysts lean towards this school. The Proshare twist is that the recapitalisation of banks should be tier-based rather than a blanket statutory imposition on all banks regardless of the size of their operations. The analysts believe that Proshare’s tier 1 report could provide a basis for classification. The analysts have, however, admonished that the banks’ recapitalisation process should be phased to avoid systemic shocks and operational dislocations.

The analysts, however, doubt the absorptive capacity of the Nigerian economy to handle banks with N800bn to N1trn capitalisation. The stock market would be in a wild growth mode out of sync with underlying macroeconomic triggers. In addition, the absence of quality loan assets to absorb the rush of new funds could lead to declining loan asset quality and a rise in nonperforming loans (NPLs).

Nevertheless, analysts like Ambrose Omordion of InvestData have argued that recapitalisation will help banks expand by financing projects that can unlock economic value. ‘Beyond buying bank shares, investors should diversify their portfolio by looking at real estate and technology,’ he argues.

In the broad scheme of things, banking sector recapitalisation appears inevitable. However, the size of the new capital base of banks and the timing of the exercise remains obscure. With banks throwing their hats, fedoras, and bonnets into the Rights Offer ring, the recapitalisation journey of local lending institutions eighteen years after the last exercise seems alive and fit.

Copied